Shukri Shehab and his wife have not slept in two nights. Their three-week-old granddaughter will not stop crying.

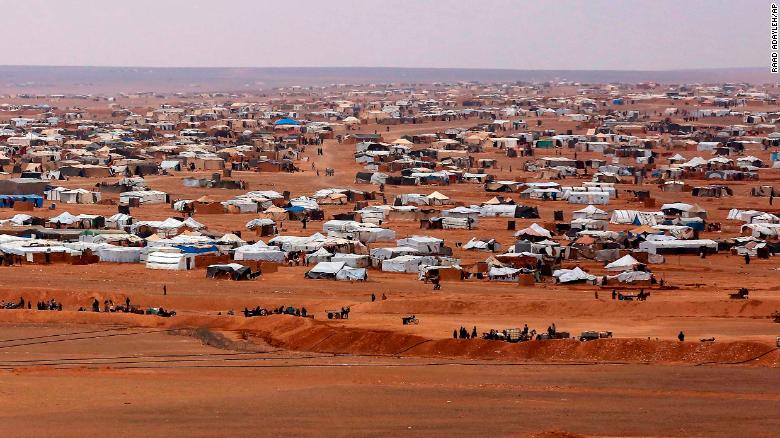

She needs simple medicine for bloating, Shehab says, but it is nearly impossible for them to find. Shehab lives in Rukban, an informal settlement for Syria's displaced people in a US-protected zone in southern Syria, roughly 10 miles away from an American military base. Shehab has been communicating with CNN over the last four months. For more than 1,200 days, Shehab says he and his family have lived in this cluster of shelters sprinkled along a stretch of desert on the Syrian-Jordanian border. Activists dubbed it the "Triangle of Death." The United Nations called conditions "desperate," "catastrophic" and "no place for a child."For years, the displaced in Rukban have been at the mercy of proxy powers and political players, leaving them with sporadic access to humanitarian aid and no safe way home. And for the past five months, the Syrian government has blocked humanitarian access to the encampment through its territories.

She needs simple medicine for bloating, Shehab says, but it is nearly impossible for them to find. Shehab lives in Rukban, an informal settlement for Syria's displaced people in a US-protected zone in southern Syria, roughly 10 miles away from an American military base. Shehab has been communicating with CNN over the last four months. For more than 1,200 days, Shehab says he and his family have lived in this cluster of shelters sprinkled along a stretch of desert on the Syrian-Jordanian border. Activists dubbed it the "Triangle of Death." The United Nations called conditions "desperate," "catastrophic" and "no place for a child."For years, the displaced in Rukban have been at the mercy of proxy powers and political players, leaving them with sporadic access to humanitarian aid and no safe way home. And for the past five months, the Syrian government has blocked humanitarian access to the encampment through its territories.

"No side is taking responsibility for these people," says Aron Lund, a Syria expert and fellow at the Century Foundation, a non-partisan think tank. A State Department official tells CNN the US is "pursuing every possible avenue to deliver aid to Rukban." But so far Washington has not directly provided aid to the tens of thousands stuck in the settlement, even though the US has protected the area since 2016. The US has pinned the blame solely on the Syrian government and its Russian allies. Damascus has denied requests for aid deliveries to Rukban since February, pushing instead for civilians to return to regime-controlled areas."Rukban is another example of the Assad regime's consistent practice, with Russian support, of facilitating the suffering of its own people while using the situation as a propaganda tool to deflect the blame for its own inhumane behaviour," Pentagon spokesperson Cmdr. Sean Robertson said in a statement. In Syria, aid is delivered either cross-border, with the consent of the neighbouring country, or through the UN and other humanitarian groups based in Damascus. But Jordan halted regular cross-border deliveries years ago, leaving only the Syrian government in control of approving UN humanitarian aid convoys to the settlement. Experts say the US can do more to help. Unlike other areas where the regime has denied or prevented humanitarian access, in Rukban "you have, within the besieged area, a US base and US access. At some point, it doesn't really work to say this is (only) the Syrian government's fault. Yes, it is, but then what?" says Lund. The US "could do things for Rukban and they're not doing it. The US could absolutely bring food and especially medicine to Rukban," Lund says."There is definitely US culpability in this. Is it only the US? No, absolutely not. But it's a situation where the US has grabbed a piece of Syria and says it is not responsible for the people in that part of Syria, which is wrong."